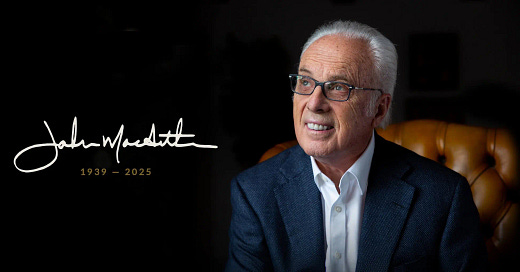

So I recently posted that we ought to pray for the repose of John MacArthur’s soul on Facebook and X. Some people had questions. After all, if MacArthur is with Christ, why pray for him? If he’s not, why pray for him?

If you’re a Roman Catholic, the answer is: “well, because if he’s going to heaven, then he’s probably in purgatory, and so praying for him alleviates temporal debt and averts the wrath of God.” Okay. That’s one answer.

I think that answer is false. But in this post, I want to list two reasons from an Anglican perspective for why we should pray for the dead. First, I believe in post-mortem opportunity. I think there are hints in Scripture and tradition that the opportunity to repent extends beyond the grave. Second, I think our worship enhances the blessedness of the saints. So let’s substantiate both of these claim.

Post-Mortem Opportunity?

For years, I was simply agnostic as to this question. Scripture does not rule out post-mortem opportunity, and I thought it really had nothing to suggest it was possible either. Typically people quote Hebrews (“it is appointed once for man to die, and then judgment”), but forget to note that the text doesn’t say “and right after death comes judgment”). Rather (and more Hebraically, I might add), there are two more decisive phases for the life of man: death, and then final judgment. So the text easily speaks moreso to the two remaining phases of human life.

So, initially, I thought Scripture leaves us in the dark about whether there is post-mortem opportunity. But then I did a little more digging.

First, it seems that a number of church fathers affirmed the possibility of postmortem repentance. In the Stromata, Clement of Alexandria writes,

“If, then, the Lord descended to Hades for no other end but to preach the Gospel, as He did descend; it was either to preach the Gospel to all or to the Hebrews only. If, accordingly, to all, then all who believe shall be saved, although they may be of the Gentiles, on making their profession there. . . . If, then, He preached only to the Jews, who wanted the knowledge and faith of the Saviour, it is plain that, since God is no respecter of persons, the apostles also, as here, so there preached the Gospel to those of the heathen who were ready for conversion. . . . What then? Did not the same dispensation obtain in Hades, so that even there, all the souls, on hearing the proclamation, might either exhibit repentance, or confess that their punishment was just, because they believed not?

One finds similar affirmations in Cyril of Alexandria and Hippolytus. Furthermore, among the universalists of the early church, Maximus the Confessor, Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, Isaac of Nineveh, and others believed that unbelievers would be converted through the cleansing fire of judgment after death. Further, in the fifth century text Life and Miracles of St. Thecla, there seems to be a clear hope for salvation after death to unbelieving pagans.

Falconilla, the daughter of (the pagan) Tryphaena who died some years prior, appears to Tryphaena in a vision, saying,

“I urge you, mother, to abandon the great grief you have on my account, and to stop weeping in vain, and to cease destroying your own soul with lamentations. For you do not benefit me at all with these things, and you might end up adding your own death to mine! Request, therefore, of Thecla, who is staying with you, and who has become a child to you in my place, that she make some intercession (presbeivan) for me to God, that I might obtain his love of humanity (filanqrwpiva") and his calm gaze, and that I might be transferred to the place of the righteous. For even here, too, the fame of Thecla is great because she struggles brilliantly and courageously for the sake of Christ. (17.7–17)”

Tryphaena, upon waking up, says this to St. Thecla:

O, my child, my God-given child, God has led you here and has cast you into my arms in order that you might alleviate completely my misfortune and join the soul of my daughter Falconilla to Christ, and that you might procure for her through your prayer what she lacks from faith (to; para; th'" pivstew" ejlleivfqen). Pray and request of Christ the King to give to you grace from himself so that my daughter might rest and have eternal life. For Falconilla herself has asked for this from you in a vision that came to me this very night. (17.24–32)

St. Thecla prays,

Christ, King of the Heavens, Child of the Great and Most High Father, who has bestowed grace upon me such that I believe in you and am saved, and who has made the light of your truth shine before me, and who has already deemed me worthy that I might suffer for you, grant also to your servant Tryphaena the fulfillment of her wish concerning her daughter. Her wish is that the soul of her daughter be numbered among the souls who have already believed in you and that she enjoy a dwelling and luxury in paradise. Make this reward payment to Tryphaena and to me, Master Christ, for behold, as you see, she has become the guardian of my virginity, she has stood beside me (in addition to your own Paul), she has snatched me from the fury of Alexander, and she has comforted me on her breast in her home after my terror with the beasts. Although she is a Queen, she has been reduced to my debased level out of desire and fear towards you. In exchange for all these things she desires and requests this: that her only and beloved child obtain some rest. (17.38–53)

This only makes sense if she (and the author of the text) believed that salvation after death for unbelievers was possible. This belief is rooted in the notion that Christ preached to the dead in the event known as “the harrowing of hell.” The Odes of Solomon, written in the early second century, frames the event from the Son’s perspective:

I was not rejected although I was considered to be so, and I did not perish although they thought it of me. Sheol saw me and was shattered, and Death ejected me and many with me. I have been vinegar and bitterness to it, and I went down as far as its depth. Then the feet and the head it released, because it was not able to endure my face. And I made a congregation of the living among his dead; and I spoke with them by living lips; in order that my word may not fail. And those who had died ran toward me; and they cried out and said, “Son of God, have pity on us. And deal with us according to your kindness, and bring us out from the chains of darkness. And open for us the door by which we may go forth to you, for we perceive that our death does not approach you. May we also be saved with you, because you are our Savior.” Then I heard their voice, and placed their faith in my heart. And I placed my name upon their head, because they are free and they are mine. Hallelujah -Odes 42:10-20

There is no evident limitation of the group who trusts in Jesus to just the patriarchs or the righteous dead. Where did they get this from Scripture? They got this from 1 Peter 3:19, which says that Christ preached to the spirits in Hades. Martin Luther, in a commentary on Hosea, explains 1 Peter 3 as follows:

“Here Peter clearly teaches that Christ not only appeared to the departed fathers and patriarchs, some of whom, without doubt, Christ, when he rose, raised with him to eternal life, but also preached to some who in the time of Noah had not believed, and who waited for the long-suffering of God, that is, who hoped that God would not enter into so strict a judgment with all flesh, to the intent that they might acknowledge that their sins were forgiven through the sacrifice of Christ.”

This seems like the most straightforward explanation of 1 Peter 3:19 and 1 Peter 4:6: Jesus Christ descended to the dead and preached the gospel to the dead that they might live.

The final judgment, remember, happens when our Lord returns and raises all people from the dead. We confess this at the end of the Apostles’ and Nicene Creed. The execution of final judgment in either eternal life or eternal condemnation will happen then. But until then, those who die outside of Christ go to Hades—the holding place of the dead. And in this holding place, as we have seen, the dead may still repent given the proclamation of Christ’s gospel even in death.

However, will they? Not necessarily. In The Great Divorce, CS Lewis depicts a Lady transformed by the grace of God encountering her former husband, Frank. Frank’s spirit, however, has been broken into a “Dwarf” and a “Tragedian”, tied together by a chain—both of them speaking as the remnants of Frank. Frank cannot get over the fact that the Lady has been content in the presence of God without him. The exchange is gut-wrenching:

“Dear, no one sends you back. Here is all joy. Everything bids you stay.” But the Dwarf was growing smaller even while she spoke.

“Yes,” said the Tragedian. “On terms you might offer to a dog. I happen to have some self-respect left, and I see that my going will make no difference to you. It is nothing to you that I go back to the cold and the gloom, the lonely, lonely streets——”

“Don’t, don’t, Frank,” said the Lady. “Don’t let it talk like that.” But the Dwarf was now so small that she had dropped on her knees to speak to it. The Tragedian caught her words greedily as a dog catches a bone.

“Ah, you can’t bear to hear it!” he shouted with miserable triumph. “That was always the way. You must be sheltered. You couldn’t bear the least sound of the one real anguish you had to go out of your sight. You let me go on, you let me go on being happy without me, forgetting me. You didn’t want even to hear of my sufferings. You say, don’t. Don’t tell you. Don’t make you unhappy. Don’t break in on your sheltered, self-centred little heaven. And this is the reward——”

She stooped still lower to speak to the Dwarf which was now a figure no bigger than a kitten, hanging on to the end of the chain with his feet off the ground.

“That wasn’t why I said, Don’t,” she answered. “I meant, stop acting. It’s no good. He is killing you. Let go of that chain. Even now.”“Acting,” screamed the Tragedian. “What do you mean?”

The Dwarf was now so small that I could not distinguish him from the chain to which he was clinging. And now for the first time I could not be certain whether the Lady was addressing him or the Tragedian.

“Quick,” she said. “There is still time. Stop it. Stop it at once.”

“Stop what?”

“Using pity, other people’s pity, in the wrong way. We have all done it a bit on earth, you know. Pity was meant to be a spur that drives joy to help misery. But it can be used the wrong way round. It can be used for a kind of blackmailing. Those who choose misery can hold joy up to ransom, by pity. You see it all the time. You were a child; you did it. Instead of saying you were sorry, you went and sulked in the attic . . . because you knew that sooner or later one of your sisters would say, ‘I can’t bear to think of him sitting up there alone, crying.’ You used your pity to blackmail them, and they gave in in the end. And afterwards, when we were married . . . oh, it doesn’t matter, if only you will stop it.”

“And that,” said the Tragedian, “that is all you have understood of me, after all these years.” I don’t know what had become of the Dwarf Ghost by now. Perhaps it was climbing up the chain like an insect: perhaps it was somehow absorbed into the chain.

“No, Frank, not here,” said the Lady. “Listen to reason. Did you think joy was created to live always under that threat? Always defenceless against those who would rather be miserable than have their self-will crossed? For it was real misery. I know that now. You made yourself really wretched. That you can still do. But you can no longer communicate your wretchedness. Everything becomes more itself. Here is joy that cannot be shaken. Our light can swallow up your darkness: but your darkness cannot now infect our light. No, no, no. Come to us. We will not go to you. Can you really have thought that love and joy would always be at the mercy of frowns and sighs? Did you not know they were stronger than their opposites?”

Frank, unfortunately, does not end up yielding to the Lady. The Dwarf diminishes into oblivion, and the Tragedian swallows the chain and the Dwarf. The creature now bears so little resemblance to Frank that the Lady no longer recognizes him.

Lewis’s point is this: the trajectories we set in our characters now will persist into eternity. I have met non-Christians who have said, “well if there’s the possibility of post-mortem repentance, then I’ll live it up now and repent later!” But this is a fool’s errand. Repentance is true and genuine contrition—true and genuine renunciation of one’s old way of life out of love for God, who is the sum of all Goodness. It is foolish to think “well I’ll just indulge in selfishness/greed/lust now and regret doing it later”—as though such regret could be genuine. Frank abused people’s pity in life as a kind of weapon with which to, as it were, force people’s expressions of care. A husband who says to his wife “oh you must have been sooo happy during your girls’ night out without me” may really be trying to flatter himself by eliciting her expression of care. That sort of manipulative tendency is a kind of poison—a cancer that, when fed, only grows. The gospel of Christ is a cure for this cancer because it forces us to live our whole lives in repentance—in the stark realization that everything we do is tainted by sin, and thus it turns us from reliance on our own goodness into humble dependence on the great Teacher and Savior. Humility and self-renunciation is therefore the beginning of genuine faith.

So it is not clear that those who lack these things now will suddenly gain them upon death. If one doesn’t see their need for Christ now, they may not see it then. And thus, we pray that God would move the living and the dead towards feeling their need of Christ.

But What About the Saints?

Okay, but suppose John MacArthur is in the presence of Jesus already? Why then should we pray for his repose? In the ancient church, there are plenty of liturgies that include prayers for those already in the presence of God. The Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom offers the Eucharist for the “fathers, patriarchs, prophets, apostles, preachers…and all the righteous perfected in faith, especially our all-holy, immaculate, highly glorious Blessed Lady, Mother of God and ever-Virgin Mary.”

But how can prayer for the dead perfect their repose? Remember, the righteous dead currently await the final resurrection. As such, their bliss is not yet complete. Hence, in prayer, worship, almsgiving, etcetera, we join together with the company of heaven in the praise of God. The bond of the Spirit is such that, when we pray for our loved ones who have gone before us, that expression of love for them itself enhances their enjoyment of Christ. One way this might work is that, in praying for the dead and expressing our love for the righteous saints gone before us, they get to see more of the heart of the Savior refracted in the people of God—which redounds to their joy. There may be a myriad of other ways our prayers aid them!

So whatever the fate of John MacArthur, let us pray for the repose of his soul and our eventual sharing with MacArthur of the joy promised to those who love Jesus Christ.

I struggle to see Hebrews 9 as being that malleable. The passage seems less about the technicalities of life stages and more about the singularity of our deaths (and thus our lives) prior to judgement - in parallel with Christs singular death prior to judgement.

If you have further argumentation I'd be keen to hear it though.

"[N]either let us dream any more that the souls of the dead are anything at all holpen by our prayers: but, as the Scripture teacheth us, let us think that the soul of man, passing out of the body, goeth straightways either to heaven or else to hell, whereof the one needeth no prayer, and the other is without redemption." The Third Part of the Homily on Prayer.

"Let us not therefore dream either of purgatory, or of prayer for the souls of them that be dead; but let us earnestly and diligently pray for them which are expressly commanded in holy Scripture, namely, for kings and rulers, for ministers of God’s holy word and sacraments, for the saints of this world, otherwise called the faithful, to be short, for all men living, be they never so great enemies to God and his people, as Jews, Turks, pagans, infidels, heretics. Then shall we truly fulfil the commandment of God in that behalf, and plainly declare ourselves to be the true children of our heavenly Father, which suffereth the sun to shine upon the good and the bad, and the rain to fall upon the just and the unjust. For which and all other benefits most abundantly bestowed upon mankind from the beginning let us give him hearty thanks, as we are most bound, and praise his Name for ever and ever. Amen." The Third Part of the Homily on Prayer.

Are you not confessional or do you interpret these words in a way that allows prayer for the dead? How do these things fit together with your post?